What is Testing?

Testing is simply code that checks to see if your code does what you want it to do.

Why do we use testing?

If you are a student, your “big” projects for class probably consist of 5 - 10 classes. When working on it, you can visualize how the whole system is interacting with itself. If you decide to add something new to the project, you probably know how to make that change in a way that breaks other parts of your code the least. Once you finish your change, you go and run your code and try to do all the things it is supposed to do to make sure you didn’t break anything. That whole testing process probably takes 5 - 10 minutes at most.

Now, imagine you are working on a project with over a million lines of code over all the files, and you are tasked with adding a feature to that project. You didn’t write these million lines of code yourself and you aren’t 100% sure how every class interacts with all the other classes. You have to just dive in to where you think the change needs to be made and make the change. Once you are confident that your change was successfully implemented, you need to check to make sure that your change didn’t have a ripple effect and break seemingly unrelated features. Feel free to spend the next 3 weeks manually checking every other feature in your project to make sure that your little change didn’t break other things.

You’re probably thinking at this point: “Hey Colin you dumbass, I get the point already. I couldn’t possibly manually test all that code so you are saying I need to automatically test that code.” And you’d be completely right! I am just showing the sheer importance of testing and how critical it is if you want to work efficiently on a large project.

Advantages of testing

From the previous section, the advantages are pretty obvious. If you write good, comprehensive tests you can be confident that your code works without having to manually test it. If you create a bug in the system, your tests will fail in the exact places where the bug was created, allowing you to more-easily find the issue and resolve it, saving you an immense amount of time. It also allows for test-driven development which I will get into more later in this post.

Disadvantages of testing

There aren’t any real disadvantages. One of the most common arguments against automated testing is the initial increased-workload of having to actually go and write the tests, which can sometimes be more code than the actual production code itself.

This argument is completely missing the main advantage of testing. While the initial investment of work is higher because of the need to write more code, the amount of work saved is much greater by taking away the need to do manual testing.

Test-driven development

This is the big one. If you are a student at a school like the one I graduated from, your introduction to testing was being told to write some methods to do some things, then write some unit tests that get 100% code-coverage over that code (Code coverage just means what percentage of lines in your production code that your tests cause to be run).

While that is a valid way of creating tests, that requires you to think about exactly what you need your code to do and come up with a plan to make your code do that thing, then write that code to execute that plan, all without knowing if you are really doing it correctly until you finish and test it.

You may be thinking at this point: “Colin, again, you dumbass. That’s literally your job as a software engineer. You are paid to know what your code is supposed to do, come up with a plan to make code do that, then execute that plan to make code that does that.” And you’d be completely right …kind of. Your job is indeed to make code that does a specific thing.

If you are assigned to make a class that converts dates into other formats of dates, it’s probably pretty easy to come up with a plan to make that code, then execute that plan.

It gets a bit harder probably if I told you to, for example, write a full simulation of a chess board to tell me all the legal moves in any given position. The requirements to decide if you are done or not seem pretty clear, but how will you write that? Probably a much harder question than for the date format feature. And you won’t know if you are on the right track until the end where you’ve programmed the rules of every piece type, made a way to put all the pieces on the board, figured out yourself what all the legal moves for a position is, then checked to see if your simulation gives those same moves. Then god-forbid your system doesn’t give the same moves? You’re gonna have a bad day.

Here’s where test-driven development can really stretch it’s legs. The basic idea stems from the question, “What if we wrote our tests first?”. How is that better than writing your tests better? Well, it forces you to think about your requirements from the most basic to the most complex. Since you don’t write your final versions of your test to start with, you start by writing the a basic test that move towards your final goal-state that fail, then write the most basic code you can that makes that test pass, then go back to the test to make it slightly more complex and fail again.

That may be a bit confusing, so we’ll go with the example of the chess simulation. The first thing you do will be writing a test that looks like this:

@Test

public void kingShouldBeAbleToMoveForwardOnEmptyBoard() {

int middleOfBoardX = 4;

int middleOfBoardY = 4;

// Pretend we have a King class that takes the

// starting position as constructor arguments

King king = new King(middleOfBoardX, middleOfBoardY);

assertThat(king.getLegalMoves()).contains([4, 5]);

}

This test just creates a King in the midle of the board, asks for it’s legal moves, then checks to see if one of them is (4, 5) (one step way from (4, 4)).

The most simple King class to make this test pass could look like this:

class King {

public int rank;

public int column;

public King(int rank, int column) {

this.rank = rank;

this.column = column;

}

public int[][] getLegalMoves() {

return [[4, 5]];

}

}

Now this code is kind of stupid, I literally hardcoded returning [[4, 5]] as my legal moves because that’s what the test was asking for. The next thing I would need to do is increase the complexity of the test by maybe looking for multiple legal moves from multiple starting positions, then increasing the complexity of my code to no longer hardcode return values and actually start figuring out what legal moves the king has.

I would continue to go back and forth between the test and the code until I was satisfied that my tests and code represented my requirements accurately, and that I tested every part of my code from the most basic to the most complex level. It also guided me through the process of not knowing how to meet a complex requirement by making me solve smaller problems like “How do I find the bordering cells to a cell on a grid” rather than “How do I find all the legal moves for a chess king?”

At the end of a project completed through TDD (test-driven development) I can be confident that my code does the minimum amount of work to meet all the requirements of my project from the most basic to the most complex levels. I will also have a comprehensive set of tests that allow me to easily use to test my code if I ever need to do any changes on this project.

At the end of a project not completed through TDD I can be confident that my code meets the most high-level requirements for the project, but I will not have a comprehensive set of tests that test all the levels from the most basic to the most complex parts of my code. If I need to change this code later and it causes my complex tests to fail, I can narrow down the problem to all of my code. I’m about to have a long day of debugging.

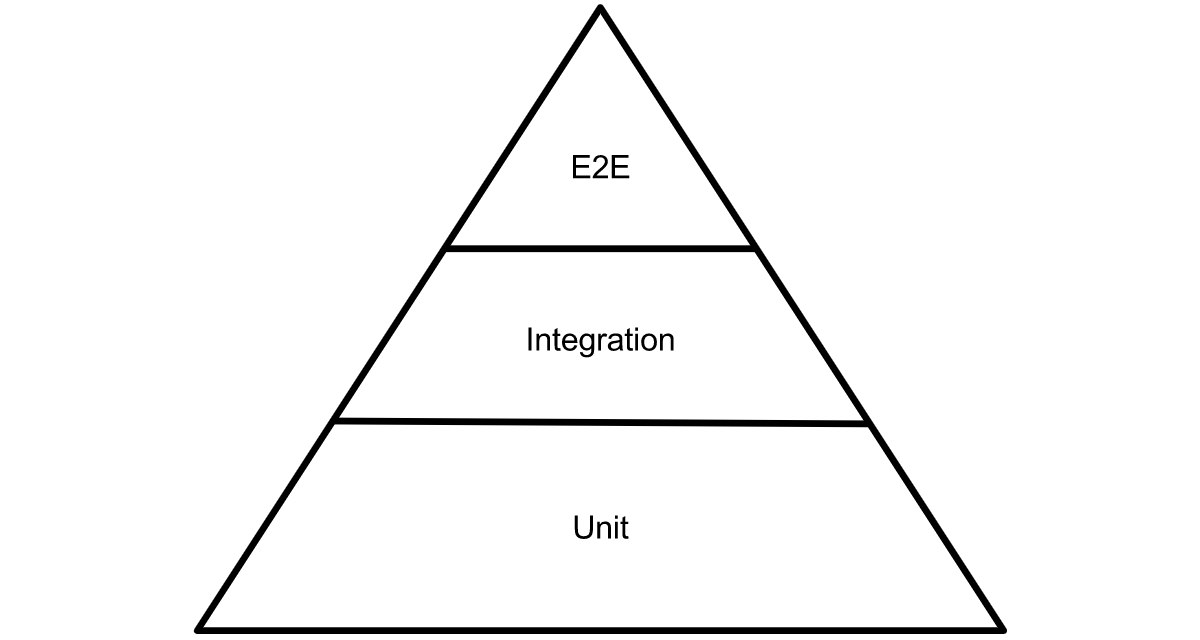

Levels of testing

I talked a lot about basic and complex tests, but what does that really mean? Well, there are three main types of tests which I classify as low, medium, and high-level testing.

Unit tests

Unit tests are the lowest-level of tests. They test to see if the module you are testing does what it is supposed to do by itself. We’ll use the chess simulation as an example. The test I showed as an example was a unit test. There were no other classes in play other than King. Those tests were purely testing to see if King does what King is supposed to do.

If you are making an API, these tests might be where you would check to see if your data classes hold data correctly.

Integration tests

Integration tests are a medium-level of testing in the sense that this is where you start to let the modules (generally classes) interact with eachother. In an integration test for the chess simulation I may test to see if the king can detect it is in check if another kind of piece is threatening it.

If you are making an API, these tests might be where you use Mockito to make fake responses from outside servers to see how your code reacts to different responses from other APIs.

End-to-end tests

E2E (End-to-end) tests are tests that completely don’t care how your code implemented the requirements. It’s only concern is that the final result looks right. In the chess example, it may play a few full game of chess against itself, attempting to make illegal moves all the time to make sure the simulation doesn’t let it make illegal moves.

If you are making an API, E2E tests generally happen in an outside tool like Postman, where you make real requests to your API and compare the API’s responses to the expected responses.